One figure, a quiet man in casual clothes, has emerged as a symbol of something different. Mahabir Pun, the new Minister of Education, Science and Technology, has long been called a one-man army scientist. He has refused the official residence. He sleeps on a cot in his ministry, cooks his own meals, and told his guards to relax.

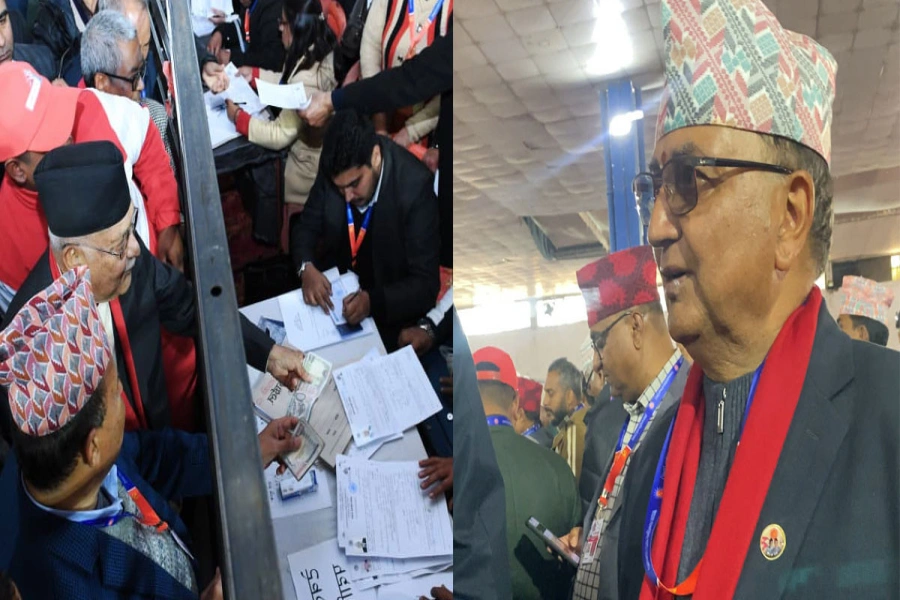

The streets of Kathmandu are still smoldering. Singha Dubar burned. So did the Supreme Court. The prime minister resigned after 22 people were killed in police clashes. The death toll has since climbed to 72. Thousands of young protesters, calling themselves Gen Z, marched with placards against corruption and privilege. They scaled walls, toppled barricades, and filled the capital with rage.

What began with a ban on 26 social media platforms including WhatsApp, Instagram, and Facebook has spiraled into something larger. The ban is gone. The fury remains. TikTok and Instagram are flooded with hashtags like #NepoKids and #NepoBaby, mocking the luxury of politicians’ children while hospitals run dry and schools crumble.”Nepal is angry. But Nepal is also searching.

And one figure, a quiet man in casual clothes, has emerged as a symbol of something different. Mahabir Pun, the new Minister of Education, Science and Technology, has long been called a one-man army scientist. He has refused the official residence. He sleeps on a cot in his ministry, cooks his own meals, and told his guards to relax.

For Gen Z, furious at corruption and excess, it is not a performance. It is proof that integrity still exists. He is a scientist, with a deep knowledge of technology and a conviction that it can serve society — a sharp contrast to the dry speeches that echo through parliament. I know this because I saw it years ago, one evening in Thamel.

A SoftBank Scout

It was 2017, just before SoftBank would pour $1.4 billion into India’s Paytm. The Japanese conglomerate was scouring Asia for new frontiers, and that evening I met Masahiro Morya, an executive in SoftBank’s New Business Section of the Business Development Department. His mandate was clear: hunt for ideas that could shape the future, meet pioneers, test their visions, and report back to Tokyo.

I had been put in touch with Masahiro Morya by my friend Nabin Risal, a senior human resources executive at Honda Japan. At the time, I was writing op-eds on emerging technology for Nepal’s leading English daily with Professor Manish Pokharel, now dean of the School of Engineering at Kathmandu University, and Professor Subarna Shakya, director of the Information Technology Innovation Center and professor of computer engineering at Tribhuvan University, who in 2019 was recognized by the World Education Congress as one of the 100 Most Dedicated Professors in South Asia. I had some credibility of my own, but more importantly, I was connected to the visionariesof Nepal’s technology scene.

Around that time, SoftBank itself was on the cusp of transforming global venture capital. Its Vision Fund, launched that year, would grow into the largest technology investment vehicle in history. Backed by Saudi billions, it would eventually invest $87.5 billion in over 90 companies — Uber, Didi, Grab, Ola, Flipkart, Coupang, Paytm, WeWork, Boston Dynamics. The strategy was breathtakingly simple: bet big, and bet on the future.

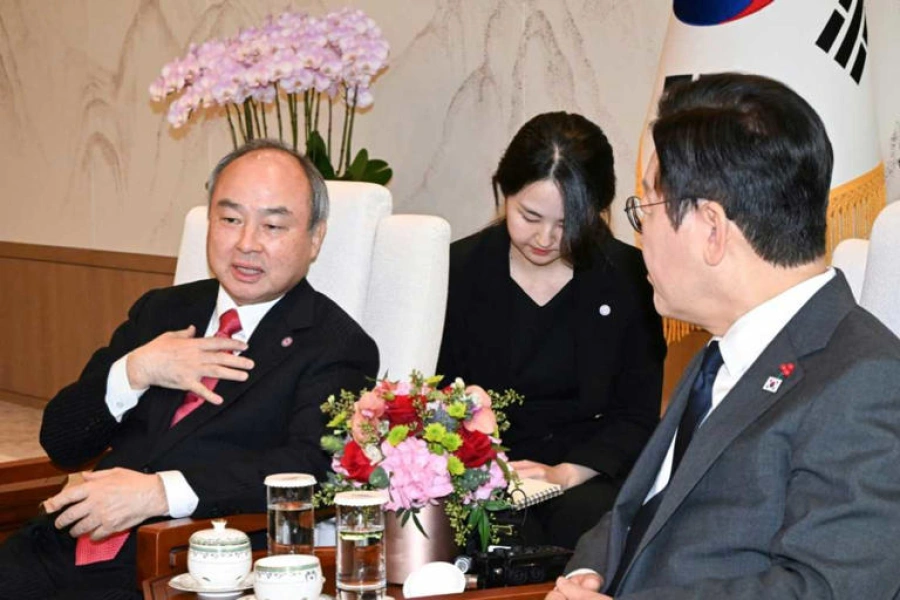

Softbank's Son says super AI could make humans like fish, win N...

Morya had come to Nepal to meet government tech leaders and pioneers, and he wanted me to arrange the introductions. I could have — I had once worked at the National Information Technology Center and, at the time, was with the World Bank–funded Nepal National Single Window Project for the Department of Customs. But I pushed for something different. If he wanted to glimpse the future, he needed to meet Mahabir Pun. That would be enough. If time allowed, then we could see Professors Pokharel and Shakya.

The Walk Across Mandala Street

Morya and I sat first at Java Café, where I laid out the trends I thought were coming: mobile-first services, digital wallets, artificial intelligence. He nodded politely, the way executives do.

Then we crossed Mandala Street to Nepal Connection, the café Pun had founded as both a business and a social enterprise. The air smelled of cardamom and conversation. It was there that everything shifted.

Pun arrived in his usual casual clothes, looking more like a schoolteacher than a man about to define a country’s technological destiny. He apologized softly for being a little late. Then he began to speak, and Morya and I fell silent. ‘Drones,’ he said simply. ‘We need them to deliver medicine to mountain villages without roads.

At the time it sounded absurd. Flying machines carrying vaccines over snowbound ridges? It felt closer to science fiction than Nepali experiment. Yet Pun spoke with clarity. He painted pictures of mothers walking for hours with sick children, of medicines spoiling on long treks, of lives that could be saved if only geography stopped dictating destiny.

Morya leaned forward. He had expected a roster of experts. Instead, he found them all in one man: the innovator, the activist, the teacher, the policy thinker. What sounded outlandish then is routine now. In China, drones drop off meals as casually as scooters once did. Amazon and other e-commerce giants are running the same experiments. But in Thamel, years earlier, Mahabir Pun was already imagining it. Even SoftBank wasn’t entirely convinced. Today, drone delivery is no longer a fantasy — it is a reality.

Drone food delivery began moving from pilot tests to real operations in the early 2020s, with pioneers like Zipline (medical supplies in Africa), Wing (Alphabet) and Flytrex (U.S. suburbs) starting commercial services by 2021–2022, and Amazon Prime Air launching limited deliveries in late 2022.

Beyond the Buzz

The talk moved on. Artificial intelligence. E-government, Crypto, Blockchain, Digital wallets. Futures still years away in Nepal.

Pun described AI tutors teaching children in remote villages without teachers. Diagnostic software helping health workers in clinics without doctors. Mobile wallets giving farmers and shopkeepers access to financial tools the banking system denied them.

For him, technology was not spectacle. It was survival. It was dignity.

A Minister in a Time of Crisis

Today, as minister, he carries the same ethos into government. He has ordered every community school to hire at least one computer teacher. He has demanded universities publish exam results within three months.

These are not sweeping reforms. They are practical steps, echoing the man who once wired mountain villages to the Internet by hand.

And then there is his decision to live inside his ministry, cooking for himself. In a country where viral videos of ministers riding in convoys of luxury SUVs stoke public rage, his humility is more than symbolic. It is a direct challenge to a culture of entitlement.

Why That Evening Still Matters

The Gen Z protesters in the streets want more than restored social media or a change in regime. They want dignity. They want economic opportunity. They want the chance to compete globally from Nepal. Above all, they want proof that privilege without service is corruption.

In Mahabir Pun, they may have found someone who reflects their values. He does not preach simplicity. He lives it. He does not theorize about technology. He builds it. He does not demand accountability. He practices it.

That is why I keep returning to that evening in Thamel. At Java Café, I spoke about global trends. Across the street, Pun spoke about futures so audacious they seemed impossible. What felt fanciful then is reality elsewhere today. The tragedy and the opportunity is that Pun imagined it first for Nepal. The greater tragedy is that his own government, at the time, was least willing to support his vision, even as a SoftBank executive sat across the table, visibly impressed.

A Future Worth Building

The question now is whether Nepal will let leaders like him translate vision into systemic change, or whether he will remain an exception in a system that rewards privilege over merit. The youth have made their demand clear. They do not want slogans. They want action.

Mahabir Pun, the one-man army scientist who wired villages in the late 1990s, flew drones over mountains, and now sleeps on a cot inside his ministry, embodies that possibility. His credibility comes not from politics but from practice. He has only six months, but I am confident something radical will emerge.

And as Nepal stands at this crossroads, the hope is simple but profound: an education system that values innovation and creativity, and a politics bold enough to do the same. Anything less would betray a generation that refuses to settle for corruption, privilege, and decline. Anything more could change the country forever.